Aboriginal Communities

Climate Change and Adaptation

Climate change impacts Aboriginal communities, their lands and resources. Aboriginal peoples are among the most vulnerable groups to climate change in the province. Climate change risks can compound or amplify many challenges already facing Aboriginal communities, including a lack of economic opportunities, poor quality housing and infrastructure, and other socio-political concerns. Indigenous and local knowledge is key to enhancing capacity to deal with climate change and other stressors, and helps foster the resilient nature, positive attitudes, community spirit and respect for Elders apparent in many Aboriginal communities.

This section of SaskAdapt.ca provides an overview of Aboriginal peoples in Saskatchewan, the challenge of climate change from an Aboriginal and science perspective, adaptation actions, and tools to assist in planning for adapting to climate change.

First Nations in Saskatchewan

With climate change already impacting on Aboriginal communities, their land and resources, how Aboriginal peoples adapt to changes in our climate is important for current and future social and economic sustainability.

Saskatchewan's Aboriginal population totals around 142,000, representing nearly 15% of the total provincial population. In northern Saskatchewan the Aboriginal population represents nearly 86% of the total population.

The majority of Aboriginal people are First Nations (91,000 or 64%) while the remainder are largely Métis (34%). See Figure 1.

Around 53% of Aboriginals in Saskatchewan live on-reserve or in rural areas, while the remaining 47% live in urban areas (e.g Regina, Saskatoon, Prince Albert; Figure 2).

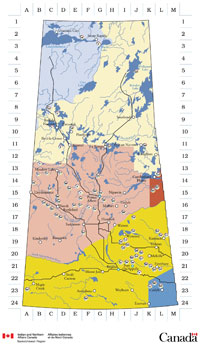

Indian and Northern Affairs Canada has prepared a booklet entitled First Nations in Saskatchewan. It provides location information for Saskatchewan First Nations Communities. The key content is replicated below: There are 70 First Nations located across the province with the majority located in the parkland or forested regions (Figures 3 and 4). Sixty-one of the First Nations are affiliated with one of nine Saskatchewan tribal councils. The five linguistic groups of First Nations in Saskatchewan are Cree, Dakota, Dene (Chipewyan), Nakota (Assiniboine) and Saulteaux.

Climate Change Impacts:

A First Nations Perspective

First Nations Elders recognize that annual variability in weather is part of the normal pattern of nature. In 2004 the Prairie Adaptation Research Collaborative (PARC) sponsored an Elders Forum on Traditional Way of Life and Climate Change in Prince Albert (Figure 5).

During the forum Elders identified several trends of concern, including the following:

- more frequent extreme weather events,

- shifts in seasonal characteristics,

- abnormally dry summers,

- increased summer heat impacting children and seniors,

- deterioration in water quantity and quality,

- changes in species distributions,

- changes in plant life and abundance of berries, and

- decreasing quality of animal pelts.

In response to changes in the availability of moose, caribou, deer, fish and wild rice, Aboriginal people may have to increase their dependence on non-traditional foods. Also, unsuitable snow and ice conditions may hamper travel to trap lines, hunting grounds and fishing areas.

One of the conclusions of the forum was a clear recognition of the need to revitalize the relationship between people and the land as a way of addressing climate change and other environmental issues.

A Science Perspective

In the latest National Assessment of Climate Change on the Prairies (Figure 6), researchers identified six key findings that apply to the Prairies generally. The findings are particularly relevant to First Nations:

- Increases in water scarcity represent the most serious climate risk.

- Ecosystems will be impacted by shifts in bioclimate, changed disturbance regimes (e.g. insects and fire), stressed aquatic habitats and the introduction of non-native plants and animals. There are implications for livelihoods and economies most dependent on ecological services (e.g. Aboriginal and forestry, respectively).

- The Prairies are losing some advantages of a cold winter. For example, oil and gas exploration and drilling sites may become less accessible and reductions in the length of winter road seasons are likely.

- Resources and communities are sensitive to climate variability and to extreme events including droughts and floods.

- Adaptive capacity, though high, is unevenly distributed. Aboriginal populations are the fastest growing and more vulnerable to health impacts. Climate change could encourage further migration from rural to urban communities.

- Adaptation processes are not well understood.

Adaptation Actions: A Perspective South of 60

The Centre for Indigenous Environmental Resources (CIER; Figure 7) prepared a national report on Climate Change and First Nations South of 60 in 2008 (Figure 8).

The report provides an introduction to climate change priorities for First Nations in the southern portion of Canada. Five priority climate impacts were identified:

- Changes to ice due to warmer weather;

- Changes to water quantity and quality;

- Changes in animal behaviour/loss of keystone species;

- Increase in frequency and severity of extreme weather events; and

- Increased frequency and severity of forest fires.

The report also presents a number of potential strategies for First Nations to adapt to climate change. The list of general adaptations include:

- Undertake comprehensive community planning that incorporates future climate change impacts in both the development of the plan and its implementation and decision making;

- Strengthen informal social networks to adapt to increased uncertainty in environmental conditions when carrying out subsistence activities;

- Undergo hazards research to determine priority hazards in the community;

- Increase energy security and opting for renewable energy sources;

- Increase economic diversification;

- Increase or obtaining insurance; and,

- Initiate climate change monitoring programs.

Other specific adaptations are suggested for each of the five priority climate impacts. These are listed in a summary report (Figure 9).

Adaptation experiences of First Nations have also been compiled by (CIER) for Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (Figure 10).

-

Figure 9: Summary Report – Climate Change and First Nations South of 60

Figure 9: Summary Report – Climate Change and First Nations South of 60 -

Figure 10: INAC Aboriginal Climate Change Adaptation Success Stories

Figure 10: INAC Aboriginal Climate Change Adaptation Success Stories

Adaptation Planning Tools for First Nations

CIER has worked in partnership with First Nations in Manitoba and Saskatchewan to develop“user-friendly and relevant climate change planning tools for First Nations in Canada”. The first communities involved in developing the tools were experiencing the effects of climate change and also beginning to address the need for their communities and people to adapt.

A series of 6 guidebooks are available to assist First Nations in their efforts to plan for extreme weather events and changes in climate:

- Starting the planning process

- Climate change impacts in the community

- Vulnerability and community sustainability

- Identifying solutions

- Taking adaptive action

- Monitoring progress and change

Each guidebook develops an important part of the planning process and is a precursor to the next guidebook. The guidebooks contain suggestions of how a First Nations community might plan for climate change, and how to involve the community in setting priorities and implementing them. The planning experiences of two communities are featured in the guidebook: Sioux Valley Dakota Nation in Manitoba and the Deschambault Lake community of the Peter Ballantyne Cree Nation from Saskatchewan (Figure 11).

The guidebooks share the experience of setting up working groups, and engaging Elders, youth, and the broader community throughout the planning process. The guidebooks also document the community’s perspective on changes in climate. A community vision is developed based on the four components of a Medicine Wheel: economic, cultural, environmental and social. For further information on the climate change planning tools for First Nations consult the CIER website (Figure 12).

Sources:

- Centre for Indigenous Environment Resources (CIER) (2006): Climate Change Planning Tools for First Nations Guidebooks. • Guidebook 1: Starting the Planning Process (661 KB) • Guidebook 2: Climate Change Impacts in the Community (863 KB) • Guidebook 3: Vulnerability and Community Sustainability (1,107 KB) • Guidebook 4: Identifying Solutions (1,106 KB) • Guidebook 5: Taking Adaptive Action (755 KB) • Guidebook 6: Monitoring Progress and Change (432 KB)

- Centre for Indigenous Environment Resources (CIER) (2008):

- Climate Change and First Nations South of 60: Impacts, Adaptation, and Priorities. Full Report. Submitted to: Indian and Northern Affairs Canada.

- Climate Change and First Nations South of 60. Summary Report. Both reports are available from http://www.cier.ca/information-and-resources/publications-and-products.aspx?id=1178 [accessed March 2, 2011]

- Centre for Indigenous Environment Resources (CIER) (2009): Climate Risks and Adaptive Capacity in Aboriginal Communities. Final Report. An Assessment South of 60 Degrees Latitude. Submitted to: Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. http://www.cier.ca/WorkArea/showcontent.aspx?id=1682 [accessed January 17, 2011]

- Ermine, W., Nilson, R., Sauchyn, D., Sauvé, E. and Smith, R. (2005): ISI ASKIWAN – the State of the Land: Prince Albert Grand Council Elders’ Forum on climate change. www.parc.ca/pdf/research_publications/FinalReportIsiAskiwanFinal1.pdf [accessed January 4, 2011]

- Ermine, W., Nilson, R., Sauchyn, D., Sauvé, E. and Smith, R. (2005): ISI ASKIWAN – The State of the Land: Prince Albert Grand Council Elders’ Forum on climate change. PARC Summary Document No. 05-04. www.parc.ca/research_pub_communities.htm [accessed January 4, 2011]

- Elliott, D. (2009): Selected Characteristics of the Saskatchewan Aboriginal Population A Presentation to: Strategies for Success Conference, June 2, 2009. Sask Trends Monitor. http://www.sasktrends.ca/Sask%20Trends%20PARWC%20June%202.pdf [accessed January 24, 2011]

- Indian and Northern Affairs, Canada (n.d.): First Nations in Saskatchewan http://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/ai/scr/sk/fni/pubs/fnl-eng.pdf [accessed January 4, 2011]

- Indian and Northern Affairs, Canada (2010): Sharing Knowledge for a Better Future - Adaptation and Clean Energy Experiences in a Changing Climate. http://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/enr/clc/cen/pubs/fbf/fbf-eng.asp#chp17 [accessed January 17, 2011]

- Merasty, G. (2010): Northern Success: Local Partnership/Global Leadership. Saskatchewan Energy Symposium, June 10, 2009. Vice President Corporate Social Responsibility, Cameco http://www.anspa.ru/files/sem2010/merasti/pres.ppt [accessed Feb. 20, 2011]

- Pittman, J. (2010): Nehiyawak (Cree) and Climate Change in Saskatchewan: Insights from the James Smith and Shoal Lake First Nations. Geography Research Forum Vol. 30 pp. 88-104.

- Sauchyn, D.J. and Kulshreshtha, S. (2008): Prairies; in From Impacts to Adaptation: Canada in a Changing Climate 2007, edited by D.S. Lemmen, F.J. Warren, J. Lacroix, and E. Bush; Government of Canada, Ottawa, ON pp. 275-328. http://adaptation.rncan.gc.ca/assess/2007/ch7/1_e.php [accessed March 15, 2010].